“Relationships are the agents of change and the most powerful therapy is human love.” (Perry & Szalavitz, 2017)

For the past 5 years now, practicing the art of psychotherapy has been – and still is – a never-ending journey of discovery and exploration for me. What led me to this profession were my own experiences, which I, at the time, did not comprehend the traumatic effects they had on my personal development. From a developmental perspective, adverse experiences can interfere with the successful resolution of the conflict in each stage, which could lead towards psychological trauma (Hoare, 2002). From an early age, my curiosity to understand certain behaviors led me towards the helping profession. Albeit with wounds of the past still amenable to meticulous care, the concept of the wounded healer resonated with me, to the point of taking steps to offer healing to clients while being healed simultaneously through introspection and therapy. My self-discovery up to now led me towards the concept of the wounded healer.

The Wounded Healer

Jung’s (1963) work was seminal in introducing the wounded healer concept as an archetype, which in order to use it, a deep knowledge of oneself is needed. This concept involves the transformational power embedded in a wounded healer (Nouwen, 1972). As Martin (2011) suggests, the best teacher is life – if we are prepared to learn and examine our lives. With introspection, the personal traumatic past of the therapist could faciliate an empathic and curative relationship with clients and a good use of countertransference (Zerubavel & Wright, 2012). As Jung (2014) puts it, good treatment is only done when the doctor deeply examines himself, “for only what he can put right in himself can he hope to put right in the patient” (p. 116). This is the meaning of the myth of Asklepios, whose pain and suffering gives him profound empathy, understanding, compassion, and insight to heal others (Kerényi, 1959).

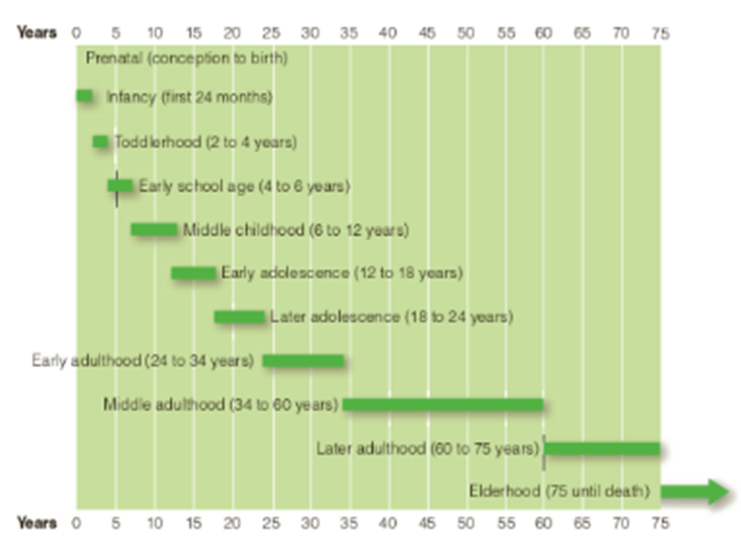

From this perspective, the wounded healer usually receives his injuries while being developed into an adult. Therefore, every period of life is characterized by specific stages, something that we call a developmental stage (Newman & Newman, 2018, p.60). These stages provide resources for mastering the challenges of the next one. At each stage, the biopsychosocial approach congregates around specific challenges requiring new perspectives on relating with society, by the integration of personal needs and social expectations (Whitbourne, Sneed, & Sayer, 2009).Therefore, in this essay, there will be an emphasis on two specific theories, Erikson’s Psychosocial Developmental Theory and Bowlby’s Attachment Theory, both in regard to trauma and healing.

Erikson’s Psychosocial Development Theory

Erikson (1963, p. 37) stated that human life is shaped by the interaction of three systems: the biological, the psychological, and the societal system. Erikson’s (1950) first stage is Trust vs Mistrust where the baby develops social trust in the ease of his food intake, the quality of his sleep, and the easing of his bowels. In a sense, the mother becomes the regulator to balance discomfort until the baby’s homeostasis is fully formed. For Erikson, the childhood period is “the scene of man’s beginning as man, the place where our particular virtues and vices slowly but clearly develop and make themselves felt” (Coles, 1970, p.139).

As Erikson puts it, is “the quality of the maternal relationship” (p. 224) that is crucial in the development of trust. The achievement of this stage is its willingness to not search for the mother because it develops the trust and certainty of the mother’s now predictable behavior. The successful accomplishment of this stage is crowned with the baby’s smile. This stage is crucial in the development of trust, because as Erikson states, it

“…implies not only that one has learned to reply on the sameness and continuity of the outer providers, but also that one may trust oneself and the capacity of one’s own organs to cope with urgers; and that one is able to consider oneself trustworthy enough so that the providers will not need to be on guard lest they be nipped” (p.220).

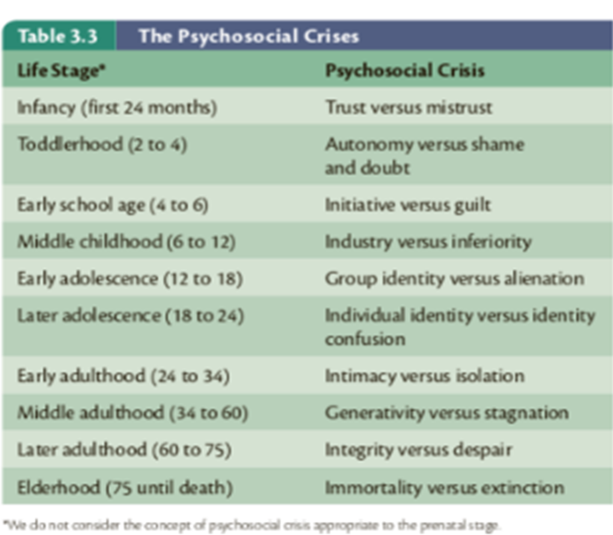

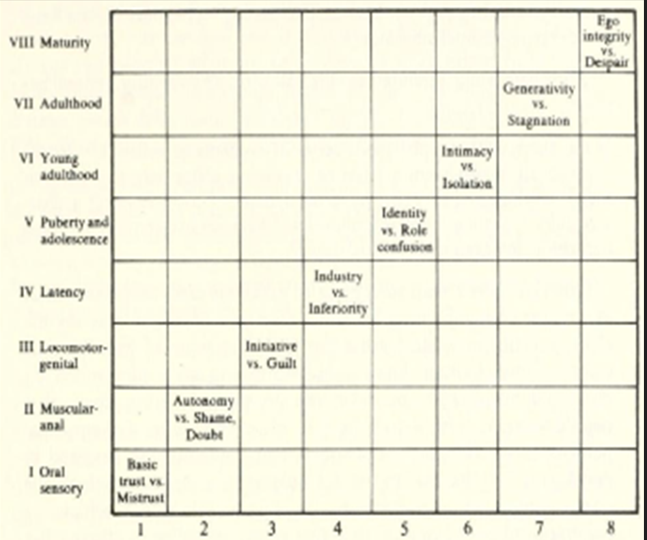

The next stage that follows is the Autonomy vs Shame and Doubt. Here, the child learns to assert its independence and find a balance between holding on and letting go (p.225). If caregivers are encouraging and setting appropriate boundaries, the child learns the virtue of will as this independence serves as protection “against meaningless and arbitrary experiences of shame and of early doubt” (p.223). Throughout the stages, certain virtues (or otherwise stated as Ego Qualities and Core Pathologies) need to be acquired (See table in Appendix 1 as copied from Newman and Newman, 2018, p. 73), something that is a life-long process of questioning and reintegration of previous stages (see Orenstein & Lewis, 2022). As this theory is very well covered in many sources (Gross, 2020; Munley, 1975; Maree, 2022; Bishop, 2013) the focus here will be on the Erikson’s overall theory of developmental stages in regard to the crises one needs to overcome in order to unlock the virtues/values of each stage. All eight stages are further illustrated on the table in Appendix 2 (copied from Erikson, 1950, p. 234).

Important here is the fact that if the conflict of a stage is overcome, competence emerges to proceed to the next one. It is noteworthy that in Erikson’s (1950) original model, there was no chronological time limit for development. Instead, he highlighted on an individual timetable, directed by biological growth and cultural expectations. His theory rests on predetermined, sequential stages, each characterized of a specific psychological conflict, something that he named, the epigenetic principle (Erikson, 1963).

Newman and Newman (2018, p. 62) critisized Erikson’s theory by finding it incomplete. They raised three criticisms of the layout by stating that each stage has different length; that transitions from one stage to another is not immediate, instead is the result of many systems taking place progressively; and that new stages could be expected as culture evolves. Consequently, Newman and Newman proposed 11 stages of psychosocial development, shown on the tables in APPENDIX 3.

Despite the resolution of Erikson’s crisis as a regular set of stresses and worries of each stage, there are unforeseen traumatic stressors such as parental divorce, death, and other losses that may lead to anxiety, defensivenes, deterioration, or fear (Newman & Newman, 2018, p. 65). A research study combining resilience with Erikson’s stages revealed that if the first three developmental stages (Trust, Autonomy, and Initiative) are successfully resolved, then the individual could endure any external stressors in a resilient manner (Svetina, 2014).

However, identity crises could happen at any given moment, since, according to Marcia (1980), identity formation is a dynamic and ongoing process helped by how the person deals with these ‘crises’. Identity can be viewed existentially as an inner organisation of abilities, needs, sociopolitical stances, and self-observations. The more developed this structure is, the more aware they are of their strength and weaknesses and of what makes them exceptional and similar to others; the less developed this structure is, the more confused they can be of their uniqueness and the more they will rely onto external evaluation. Hence, Marcia identified four modes of identity that follow after the “decicion-making period (crisis)” and the degree of personal commitment: identity achievement, foreclosure, identity diffusion, and moratorium.

Identity Achievements are the ones who have overcome a decision-making period/crisis and are pursuing the chosen profession and/or ideology. Foreclosures are those who have not been through a crisis and not committed to an ideology or profession but these were chosen by their family. Identity Diffusions are the people who despite going through a crisis, they lack any specific commitment to any ideology or profession. Lastly, Moratoriums are individuals who are actively going through a crisis, and their commitment to a specific occupation/ideology is still vague.

It is noteworthy that Erikson argued that developmental concerns emerge, intersect with previous stages, and continue after other stages appear. These resolutions are partial, as Erikson suggests, and may even be transient. Consequently, developmental concerns may re-surface and previous resolutions may be challenged (Stewart & Newton, 2010). While this challenging process takes place, the individual takes a good look at their own traumatic histories and develops from a wounded healer to a healing “minister.” As Nouwen (1972, p. 96) stated, “making one’s own wounds a source of healing” calls for a fixed readiness to “see our own pain and suffering as rising from the depth of the human condition that we all share” therefore accepting those developmental crises as part of our human condition.

Bowlby’s Attachment Theory

Moving on to Bowlby’s theory, it is interesting how he frames the losses occurring in childhood as traumatic in terms of attachment and losses (Bowlby, 1982a, pp. 14-16) and how the mother plays a significant role in the child’s development (Bowlby,1982b). Together with the contributions of Mary Ainsworth with the Strange situation, they have created an attachment theory with therapeutic value (Bretherton, 1992).

Bowlby’s contribution in regard to attachment revolved around the physical proximity to the caregiver – usually the mother. This “attachment behavioral system”, as he called it, is a way to enhance the baby’s survival. Threat and insecurity would, therefore, motivate the child to seek solace and security in the presence of its caregiver (Wallin, 2007, p.12). Despite giving less priority to the father-child relationship by assuming that he is providing the mother with love and companionship and all things necessary for her to provide to the child, Bowlby (1951, p. 13) emphasizes that it is the relationship with the mother the most important factor here for the child’s healthy upbringing.

Based on up-to-date research (Opie, et al., 2021; Tabachnick, He, Zajac, Carlson, & Dozier, 2022; Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, 1978) secure attachment happens when the mothers developed emotional attunement with their child, accepting the child’s temperament, cooperating with it, and being emotionally available.

Using the Strange Situation (Ainsworth et. al., 1978), childhood trauma is created by separation and loss from the mother, which can eventually lead to an avoidant attachment style. As Wallin (2007) noted, any of the children’s “bids for connection” where rejected by the mother, leading the child to give up trying and become avoidant instead.

Next, Ainsworth et. al., (1978) described the ambivalent attachment style, as occuring when babies had mothers who were unpredictable and at times unavailable for emotional attunement. Their expressions were amplified and they were preoccupied on the mother’s availability without being emotionally regulated (Wallin, 2007, p.21).

Lastly, an additional contribution to the attachment theory was the Disorganized attachment style, developed by Main (1995). She hypothesized that this style is a consequence of a parent who acts simultaneously both as a safe haven and a source of danger and threat – something that confuses the child.

Research has shown how trauma can affect the child’s life tremendously (van der Kolk, 2005). Van der Kolk summarized in his research how important it is for caregivers to create a safe and supportive environment for the child. Failure to do this may result in emotional dysregulation; distress; lack of trust in finding solace in the environment; precipitating dissociative states of communication (i.e. spacing out); and insecurity in the attachment bond.

Conclusions And Concluding Thoughts

These developmental theories could be further expanded and discussed endlessly. However, for the brief word limits of this essay, it was essential to transfer the gist of the theories and connect it with the wounded healer concept as it applies to psychotherapy. Nouwen’s (1972) understanding of the wounded healer shows how the wounds of the minister could work as catalysts of inner change, leading towards a compassionate understanding of interpersonal issues.

Studies have shown that the therapeutic relationship is very crucial despite specific therapeutic schools of thought. For example, the manner in which mental health professionals interact with patients is essential for the formation of trust. As Howe, Leibowitz, and Crum (2019) state, this compassionate interaction generates the thought that the therapist “gets it” and s/he “gets you”. Gelso and Carter (1985, 1994) define this relationship as “the feelings and attitudes that therapist and client have toward one another, and the manner in which these are expressed”.

From the developmental perspective of Erikson’s and Bowlby’s theories, we need to go through specific crises before we unlock the virtues/values of each stage. The successful resolution of this leads us towards developing a safe attachment with a caregiver. This social aspect of interaction and attunement, leads children to interactively regulate their nervous system until they learn to self-regulate. Therefore, a secure attachment can have positive effects on the child’s developing brain (see Schore, 2001, and Siegel, 2020, for extended discussion).

Recognizing the stages and crises, as well as the psychological challenges of healing, the wounded healer’s abilities to listen (Jackson, 1992) are intensified not to only gather information, but to humanistically and empathically approach the patient with an“I get you” mentality, walking together through the trenches on the client’s psyche towards growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). For this to happen, we as therapists, are responsible to create a safe sanctuary for both our clients and ouselves, because healing is an ongoing and interactive process, and as Perry and Szalavitz (2017, p. 230) state “…the most powerful therapy is human love” embedded in the way we socially communicate.

References

Ainsworth, M. D., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Erlbaum.

Bishop, C. L. (2013). Psychosocial stages of development. . The encyclopedia of cross-cultural psychology, 1055-1061.

Bowlby, J. (1951). Maternal care and mental health (Vol. 2). Geneva: World Health Organization.

Bowlby, J. (1982a). Attachment and Loss: Vol. 1. Attachment (2nd ed.). New York: Basic Books.

Bowlby, J. (1982b). Attachment and loss: retrospect and prospect. American journal of Orthopsychiatry, 52(4), 664-678.

Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 759-775.

Coles, R. (1970). Erik H. Erikson: The Growth of His Work. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and Society. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. .

Erikson, E. H. (1963). Childhood and society (2d ed., rev.). New York: W. W. Norton.

Gelso, C. J., & Carter, J. A. (1985). The relationship in counseling and psychotherapy: Components, consequences, and theoretical antecedents. The Counseling Psychologist, 13, 155–243.

Gelso, C. J., & Carter, J. A. (1994). Components of the psychotherapy relationship: Their interaction and unfolding during treatment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 41, 296–306.

Gross, Y. (2020). Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. . The wiley encyclopedia of personality and individual differences: Models and theories, 179-184.

Hoare, C. H. (2002). Erikson on development in adulthood: New insights from the unpublished papers. New York: Oxford University Press.

Howe, L. C., Leibowitz, K. A., & Crum, A. J. (2019). When your doctor “gets it” and “gets you”: The critical role of competence and warmth in the patient–provider interaction. Frontiers in psychiatry, 10(475), 1-22.

Jackson, S. W. (1992). The listening healer in the history of psychological healing. American Journal of psychiatry, 149, 1623-1623.

Jung, C. (1963). Only the wounded physician heals. In Memories, Dreams, Reflections. An Autobiography. London: RKP.

Jung, C. (2014). Collected works of CG jung, volume 16: Practice of psychotherapy. (H. Read, M. Fordham, G. Adler, W. McGuire, Eds., & R. Hull, Trans.) Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kerényi, K. (1959). Asklepios: Archetypal image of the physician’s existence. Archetypal images in Greek religion (Vol. 65).

Main, M. (1995). Attachment: Overview, with implications for clinical work. Attachment theory: Social, developmental, and clinical perspectives , 407-474.

Marcia, J. E. (1980). Identity in adolescence. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, 9, 159-187.

Maree, J. G. (2022). The psychosocial development theory of Erik Erikson: critical overview. The Influence of Theorists and Pioneers on Early Childhood Education, 119-133.

Martin, P. (2011). Celebrating the wounded healer. Counselling Psychology Review, 26(1), 10-19.

Munley, P. H. (1975). Erik Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development and vocational behavior. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 22(4), 314-319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076749

Newman, B., & Newman, P. (2018). Development Through Life: A Psychosocial Approach. Thirteenth Edition. Boston: Cengage Learning.

Nouwen, H. J. (1972). The Wounded Healer: Ministry in Contemporary Society. Second Edition: Text Complete, Updated, and Unabridged. New York: Image .

Opie, J. E., McIntosh, J. E., Esler, T. B., Duschinsky, R., George, C., Schore, A., . . . Greenwood, C. (2021). Early childhood attachment stability and change: A meta-analysis. Attachment & Human Development, 23(6), 897-930.

Orenstein, G. A., & Lewis, L. (2022, November 7). Eriksons stages of psychosocial development. Orenstein GA, Lewis L. Eriksons Stages of Psychosocial Development. [Updated 2022 Nov 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556096/. Florida: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. From https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK556096/

Perry, B. D., & Szalavitz, M. (2017). The boy who was raised as a dog: And other stories from a child psychiatrist’s notebook. What traumatized children can teach us about loss, love, and healing. UK: Hachette.

Schore, A. N. (2001). The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22(1-2), 201-269.

Siegel, D. J. (2020). The developing mind: How relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. Third Edition. . New York: Guilford Publications.

Stewart, A. J., & Newton, N. J. (2010). Chapter 26. Gender, Adult Development, and Aging. (J. Chrisler, & D. McCreary, Eds.) Handbook of Gender Research in Psychology: Volume 1: Gender Research in General and Experimental Psychology, 559-580.

Svetina, M. (2014). Resilience in the context of Erikson’s theory of human development. Current Psychology, 33, 393-404.

Tabachnick, A. R., He, Y., Zajac, L., Carlson, E. A., & Dozier, M. (2022). Secure attachment in infancy predicts context-dependent emotion expression in middle childhood. Emotion, 22(2), 258-269.

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1-18.

van der Kolk, B. A. (2005). Developmental trauma disorder: Towards a rational diagnosis for children with complex trauma histories. Psychiatric Annals, 35(5), 401-408.

Wallin, D. J. (2007). Attachment in psychotherapy. New York : Guilford Press.

Whitbourne, S. K., Sneed, J. R., & Sayer, A. (2009). Psychosocial development from college through midlife: A 34-year sequential study. Developmental psychology, 45(5), 1328-1340.

Zerubavel, N., & Wright, M. O. (2012). The dilemma of the wounded healer. Psychotherapy, 49(4), 482-491.