Values is a subject that we encounter every day in our lives; they are embedded in our choices, and they frequently direct us and motivate us towards specific goals. As a metaphor, the way that values seem to be framed are like the foundations upon which a house can be built, and then the rest follows. If the house is based on strong foundations, then the possibilities of breaking down from external phenomena is greatly reduced. Therefore, due to the intricate ways values are used and govern human behavior, and especially their use in therapy, I have chosen to base this current essay upon and briefly discuss this fascinating topic from the perspective of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).

This essay will begin with a very short description of the evolution of CBT towards 3rd wave behavior therapy, and then view values from the ACT perspective. The essay will continue with a short description on Schwartz’s (2012) theory on values and how they influence the decision making process and actions and then conclude on a short discussion on the association of values with existential therapy.

ACT as a 3rd Wave CBT

Behavior therapy can be organized into three waves which Hayes (2004b) describes as “a set or formulation of dominant assumptions, methods, and goals, some explicit, that help organize research, theory, and practice”. The first wave of behavior therapy was based on mostly scientific foundations and principles that could be tested following the scientific methods of classical and operant conditioning (Winters & Schneiderman, 2001).

It was only when this approach failed to explain the mediational assets between stimulus and response that could help to shell light to human behavior. Hence, based on the work of Aaron Beck, the cognitive part of behavior along with the techniques to alter and challenge dysfunctional beliefs, led to the birth of the 2nd wave of behavior therapy (Beck, 1997).

However, classical CBT, had some limitations concerning existential questions such as the meaning of life, meaning of values, transcendence, importance of experiences, acceptance of change, and other issues concerning existence (Prasko, Mainerova, Jelenova, Kamaradova, & Sigmundova, 2012). These limitations have been identified by both ACT and existential therapy.

As we know so far, ACT was born from the evolution of CBT, albeit with its own notable differences. Based on contextual behavioral science (see Hayes & Levin, 2009), ACT has provided a more parsimonious approach to therapy (Ciarrochi & Bailey, 2008). This approach focuses on the belief that psychological suffering is caused by experiential avoidance, cognitive fusion, and psychological rigidity which consequently leads the individual to fail to take steps in accordance with his/her values (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 2009). The core therapeutic processes towards psychological flexibility involves Acceptance, the Self-as-Context, Cognitive Defusion, Contact With The Present Moment, Committed Action, and Values – which is the theme of this essay (Hayes, 2004; Harris, 2019a).

ACT and Values

From the ACT perspective, values are paths taken where the individual judges as personally meaningful, significant, never-ending, purposeful, and vital (Stoddard & Afari, 2014). The core foundation of ACT – where Russ Harris has named the bedrock – is to develop psychological flexibility to live a rich and meaningful life (Harris, 2019b). To do so, one should develop the ability to live life from a values point of view.

In a nutshell, values are descriptions on how we want to behave; the desires on how we would like to treat ourselves, other people, and the world in general. The aim here is to clarify our values in order to guide us, direct us, and inspire us to take some action that has meaning and is goal-oriented. This way, when our internal compass is confused, we can turn inwards to get guidance and motivation, and devise an action plan which corresponds to acceptance facilitation and living a richer life with meaning and fulfilment (Harris, 2019b).

Values can be broken down into three parts: ongoing action, global qualities, and desired values (Hayes, Bond, Barnes-Holmes, & Austin, 2006). These are analyzed as following:

- Ongoing action. Values are seen as a behavior that is ongoing and that they do not stop at a goal. For example, if one chooses to be loving, caring, honest, fair, authentic, compassionate, etc., then these qualities ought to continue existing once the goal (i.e., having a partner, securing a business deal, etc.,) has been met. In other words, the values one chooses to have, do not end once the goal is achieved; they continue to be ongoing and existent.

- Global qualities. Our chosen values ought to have a quality of action which is global. What is meant by that is that a value should have qualities that unite various patterns of actions. For example, if one chooses to be fair, there are many actions he/she can take that exhibit this value. If one chooses to be a knowledgeable therapist, the choice itself is a value, and it is an ongoing action. Being a skilled, supportive, kind, and compassionate therapist, however, is a quality of action. If the value here is to be knowledgeable, then there are many different actions that demonstrate the quality of knowledge, such as kindness, compassion, interpersonal skills, empathy, etc.

- Desired. Values are desired actions in the sense that we choose to have them. They are not actions that should or must do, or ideal action to take. They are assertions on how we want and choose to behave.

After distinguishing what values are, it can be helpful to distinguish what values are not. For example, values are not a feeling state (i.e., feelings of calmness, pain-free, tensionless, no-anxiety, etc.). We could, instead, focus on the underlying value associated with the feeling state. This could create a discussion on the client’s behavior and give us some insight on the patterns of the client’s experiential avoidance (Stoddard & Afari, 2014, p. 128).

Additionally, values are not about how others are treating us. For example, a client might say that their desire is to be respected, loved, or included in a group. These things, however, are beyond one’s control. Instead, values are choices one makes that lead their actions. If one chooses to be compassionate or loving, then there is a high likelihood that this is not being reciprocated. In such a case, the ACT therapist offers validation and encouragement on continued acceptance and further engagement with their ongoing values (Stoddard & Afari, 2014, p. 128).

Values Vs. Goals

The basic differentiation between values and goals is that goals have a finite composition whereas values are infinite and never-ending. Goals are like tasks, they can be crossed-off a list, but a value is something that remains. In therapy, it is important to explain that values come with the trait of here-and-now, whereas goals are concerned about a point in the future. Values do not need to be justified due to the reason that they are statements about how we want to behave, whereas our actions do have an explanation (Harris, 2019b, pp. 214-215; Stoddard & Afari, 2014).

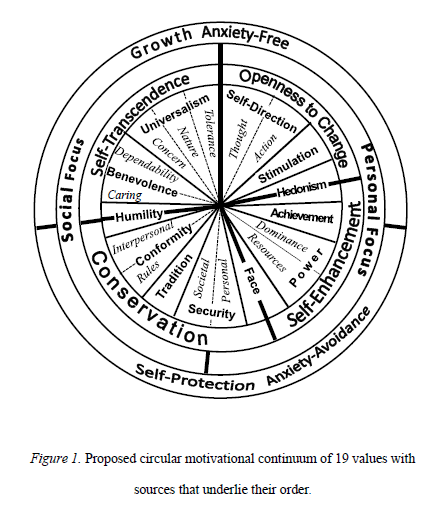

Contrary to the belief that our values should always be constantly operating on a front, on a given situation our values need to be prioritized (Harris, 2019b, p. 216). Schwartz (2012) in his theory of basic values demonstrated that choosing one value may contravene in the choice of another. Using an example Harris states, the value of being loving and caring towards our parents is not prioritized when they become abusive and hostile towards us. Instead, the value of self-protection is prioritized. That being said, it does not mean that the value of caring has vanished. Instead, it has become secondary at that given moment. It is noteworhty to cite Schwartz, et al., (2012) work on individual values as they refined their theory to express that “values form a circular motivational continuum” based on 19 universal and transcultural values. As Schwartz, et al., propose, these basic values are organized into a logical system that can be used to explain the decision making process, the attitudes and behavior of individuals which often leads to psychological dissonance and anxiety. The following figure illustrates their work.

Furthermore, according to Harris (2019b), values are to be held lightly, even if we pursue them vigorously. Values are there to give us guidance, but from the perspective of ACT, we do not want to fuse with them. If we are to follow our values rigidly, then we run the risk of being oppressed and restricted by them, leading us to take actions from a cognitive distortions’ perspective. All-or-nothing thinking, oughts/shoulds/musts, and following an absolutistic thinking is contrary to us having a virtuous and psychologically flexible mindset. As Harris mentions, using the metaphor of a compass, when we are on a journey, we do not focus all the time on the compass we are holding. Instead, we carry it in our backpacks and take it out only when we need to get some guidance to find our way (Harris, 2019b, p. 235).

Values Alone as a Factor of Change

Despite the fact that values have been a cardinal part in ACT, it has been shown by research that following a values-based approach alone may lead towards a positive behavior change (Hebert, Flynn, Wilson, & Kellum, 2021). Specifically, incorporating a values component towards the treatment of chronic pain, was shown to increase pain tolerance and enhancement in life engagement (Branstetter-Rost, Cushing, & Douleh, 2009; Matheus & Caserta, 2020); increased tolerance towards suffering (Gloster, et al., 2017); and can be used to improve distress tolerance and openness to difficult situation when faced with pain and distress perceptions (Smith, et al., 2019).

Values exploration exercises has not only been helpful in increasing pain and distress tolerance, but it appears to also be beneficial towards increasing GPA grades in students (Chase, et al., 2013). Chase, et al., have demonstrated that merely setting goals at school do not improve GPAs. Instead, a combination of goal setting and training on values had a positive impact on GPAs over the semester.

Interestingly, having our values in check has a significant contribution towards our health as well. In a laboratory experiment, researchers have tested the physiological responses of people who were repeating self-affirmations to themselves and found out that “self-enhancers” had lower cardiovascular reactions to stress, fast cardiovascular recovery, and lower baseline cortisol levels (Taylor, Lerner, Sherman, Sage, & McDowell, 2003). Additionally, strong self-resources (such as self-esteem, etc.) together with personal values, creates mental protection against stress (Creswell, et al., 2005). Creswell, et al., also confirmed that “value affirmations alone was sufficient to buffer participants’ neuroendocrine responses to stress, and this effect did not depend on dispositional self-resources” (p.850).

Even as an add-on in mindfulness interventions, value-based action and clarification of values can greatly enhance the therapeutic outcome (Christie, Atkins, & Donald, 2017). This suggests that orienting our inner compass to locate our values, can even enhance our mindfulness and being in the here-and-now, as one of the core processes of ACT.

ACT and Existential Therapy

The value-based approach of ACT seems to be a part of the Existential paradigm as well. Some researchers would even pose the question of ACT as an existential approach to therapy (Ramsey-Wade, 2015). As it is the case with logotherapy, the ideology between the two is similar regarding human suffering and the incorporation of values in therapy (Sharp, Schulenberg, Wilson, & Murrell, 2004).

Following Nietzsche’s thesis, if we want to learn about one’s philosophy, we should ask first what his values are. From the existential perspective, psychological flexibility is compromised if there is lack of values and confusion between values and goals (Prasko, Mainerova, Jelenova, Kamaradova, & Sigmundova, 2012). Existential therapy builds upon the tenet on broadening the client’s values system based on three main categories: creative values, experiential values, and attitudinal values [see Prasko, et al. (2012), pp 9-12, for more analysis]. When values are clarified and the inner compass is adjusted, then self-awareness, self-reflection, and self-improvement make more sense as concepts.

Conclusion

This essay attempted to tackle the values component of ACT, as a technique that offers contemplation and introspection. Talking about values in therapy, not only brings forth a productive discussion of things that make sense to the client, but also forms the basis and foundations to lay their thoughts and behaviors. The exploration of values has also its association to existential therapy, and it is crucial to use in-treatment and urge the client to accept the consequences of the values they prioritize, which could either lead them towards growth, transcendence, and openness to change, or towards conservation, neurosis, and distress.

References

Beck, A. T. (1997). The past and future of cognitive therapy. The Journal of psychotherapy practice and research, 6(4), 276-284.

Branstetter-Rost, A., Cushing, C., & Douleh, T. (2009). Personal values and pain tolerance: Does a values intervention add to acceptance? The journal of pain, 10(8), 887-892.

Chase, J. A., Houmanfar, R., Hayes, S. C., Ward, T. A., Vilardaga, J. P., & Follette, V. (2013). Values are not just goals: Online ACT-based values training adds to goal setting in improving undergraduate college student performance. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 2(3-4), 79-84.

Christie, A. M., Atkins, P. W., & Donald, J. N. (2017). The meaning and doing of mindfulness: The role of values in the link between mindfulness and well-being. Mindfulness, 8(2), 368-378. doi:DOI 10.1007/s12671-016-0606-9

Ciarrochi, J., & Bailey, A. (2008). A CBT-practitioner’s guide to ACT: How to bridge the gap between cognitive behavioral therapy and acceptance and commitment therapy. . Oakland: New Harbinger Publications.

Creswell, J. D., Welch, W. T., Taylor, S. E., Sherman, D. K., Gruenewald, T. L., & Mann, T. (2005). Affirmation of personal values buffers neuroendocrine and psychological stress responses. Psychological science, 16(11), 846-851.

Gloster, A. T., Klotsche, J., Ciarrochi, J., Eifert, G., Sonntag, R., Wittchen, H. U., & Hoyer, J. (2017). Increasing valued behaviors precedes reduction in suffering: Findings from a randomized controlled trial using ACT. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 91, 64-71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.01.013

Harris, R. (2019a). Chapter 1. The Human Challenge. In ACT Made Simple, Second Edition. A Quick-Start Guide to ACT Basics and Beyond. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Harris, R. (2019b). Chapter 19: Know What Matters. In ACT Made Simple, Second Edition. A Quick-Start Guide to ACT Basics and Beyond (pp. 212-227). Oakland: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Hayes, S. (2004a). Acceptance and commitment therapy and the new behavior therapies: Mindfulness, acceptance, and relationship. In S. Hayes, V. Follette, & M. Linehan (Eds.), Mindfulness and acceptance: Expanding the cognitive-behavioral tradition (pp. 1-29). New York: The Guilford Press.

Hayes, S. C. (2004b). Acceptance and commitment therapy, relational frame theory, and the third wave of behavioral and cognitive therapies. Behavior therapy, 35(4), 639-665.

Hayes, S. C., Bond, F. W., Barnes-Holmes, D., & Austin, J. (Eds.). (2006). Acceptance and mindfulness at work: Applying acceptance and commitment therapy and relational frame theory to organizational behavior management . New York: The Haworth Press.

Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2009). Acceptance and commitment therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Hayes, S., & Levin, M. (2009). Chapter 1. ACT, RFT, and Contextual Behavioral Science. In J. T. Blackledge, J. Ciarrochi, & F. Deane (Eds.), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Contemporary Theory, Research, and Practice. Australian Academic Press.

Hebert, E. R., Flynn, M. K., Wilson, K. G., & Kellum, K. K. (2021). Values intervention as an establishing operation for approach in the presence of aversive stimuli. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 20, 144-154.

Matheus, R. G., & Caserta, G. M. (2020). A Systematic Review of Values Interventions in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. International Journal of Psychology & Psychological Therapy, 20(3), 355-372.

Prasko, J., Mainerova, B., Jelenova, D., Kamaradova, D., & Sigmundova, Z. (2012). Existential perspectives and cognitive behavioral therapy. Activitas Nervosa Superior Rediviva, 54(1), 3-14.

Ramsey-Wade, C. (2015). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An existential approach to therapy? Existential Analysis, 26(2).

Schwartz, S. H. (2012). An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1116

S Schwartz, S. H.; Cieciuch, J.; Vecchione, M.; Davidov, E.; Fischer, R.; Beierlein, C.; Ramos, A.; Verkasalo , M. ; Lönnqvist, JE; Demirutku, K.; Dirilen-Gumus, O. ; Konty, M.; (2012). Refining the theory of basic individual values. Journal of personality and social psychology, 103(4), 663-688. doi:https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-66833

Sharp, W., Schulenberg, S. E., Wilson, K. G., & Murrell, A. R. (2004). Logotherapy and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): An Initial Comparison of Values-Centered Approaches. International Forum for Logotherapy, 27(2), 98-105.

Smith, B. M., Villatte, J. L., Ong, C. W., Butcher, G. M., Twohig, M. P., Levin, M. E., & Hayes, S. C. (2019). The influence of a personal values intervention on cold pressor-induced distress tolerance. Behavior modification, 43(5), 688-710.

Stoddard, J. A., & Afari, N. (2014). Chapter 7: Values. In The Big Book of ACT Metaphors. A Practitioner’s Guide to Experiential Exercises & Metaphors in Acceptance & Commitment Therapy (pp. 127-150). Oakland: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Taylor, S. E., Lerner, J. S., Sherman, D. K., Sage, R. M., & McDowell, N. K. (2003). Are self-enhancing cognitions associated with healthy or unhealthy biological profiles? Journal of personality and social psychology, 85(4), 605-615.

Winters, R. W., & Schneiderman, N. (2001). Autonomic classical and operant conditioning. In International Encyclopedia of Social & Behavioral Sciences (pp. 998-1002). University of Miami.