Creativity. A word that describes the wonder of the human existence. The imaginative capacity and vast narrative of the process of creativity has been in the questions of the humankind – if not the most important question that puzzles all disciplines and subjects in humanities and science. It appears that the phenomenon of creativity has been troubling people ever since we have started using language to communicate and build shelters and weapons to defend ourselves from animals and the furies of nature. Research on creativity has been touched by many writers and researchers in the discipline of psychology, producing handbooks on creativity (Kaufman & Sternberg, 2010; Sternberg, 1999; Runco, 1997) as well as an encyclopedia, with 232 chapters on a multidisciplinary approach to creativity (Runco & Pritzker, 2020). From the philosophical perspective, however, there has not been much discussion. Nevertheless, during the last twenty years or so, there has been an outward trend toward the philosophy of creativity, and the trend is gaining momentum progressively (Gaut & Kieran, 2018).

Since creativity has become such a vast subject to explore, in this essay there will be an attempt to explore a tiny fraction of the creative process, specifically from Rollo May’s point of view, based on his book The Courage to Create (May, The Courage to Create, 1975). Specifically, due to the word limit, there will be a brief review from May’s perspective on the creative encounter and a very brief exploration of the existential therapeutic encounter.

Creative Courage

Rollo May, in the preface of his book, expressed his ponderings regarding the “mystery of creation” towards the rendering of the book’s title. As he described, the title was influenced by Paul Tillich, who suggested the title The Courage to Be. However, this ignited his thinking process into pondering that “one cannot be in a vacuum” and that “we express our being by creating”. As he further stated, for creativity to be expressed, courage needs to be exercised. And this is what he referred to as “creative courage”.

In order, however, to exercise creative courage, an important distinction needs to be made. Having courage, does not only mean that we are undoubtedly committed towards a specific action. As May (1975) stated, “we must be fully committed, but we must also be aware at the same time that we might possibly be wrong” (p.20). He further posited that the person who exercises courage is the one who proceeds “in spite of doubt” (p.21). As he mentioned, in every thesis we always find some antithesis, and it is here where synthesis is created. The ambivalence of committing towards action in spite of doubt, is something that leads us towards the so-called, “creative courage”, in which is the uncovering of new forms, symbols, and patterns upon which a society can be created.

What Is Creativity?

Rollo May’s (1975) definition of creativity is distinct from the superficial aestheticism, which he called a “pseudo form” and “the process of bringing something new into being” in which he called the “authentic form” (p.39). He added that the process of creativity is not a product of mental illness but a process that embodies “the highest degree of emotional health, as the expression of the normal people in the act of actualizing themselves”. It is noteworthy that since May’s published book in 1975, more than 42 definitions of creativity exist (see Kampylis & Valtanen, 2010). For the sake of this assignment’s thesis, Walia (2019) has produced a very dynamic definition of creativity which resonates with May’s definition:

Creativity is an act arising out of a perception of the environment that acknowledges a certain disequilibrium, resulting in productive activity that challenges patterned thought processes and norms, and gives rise to something new in the form of a physical object or even a mental or an emotional construct. (p.242)

This creative dynamic is spilled over to the creative encounter, as defined by Rollo May.

The Creative Encounter

Proposed by Rollo May (1975, pp 40-41), the first thing that jump-starts the authentic form of creativity is called the encounter. As he explained, the creator encounters an idea or vision from different perspectives and is getting absorbed in it. In this absorption, as May noted, the creator is “being caught up in, wholly involved” and therefore, “genuine creativity is characterized by an intensity of awareness, a heightened consciousness” (p.44-50). This description is similar in line with Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi’s (2014) research on the concept of flow, with the fully dedicated involvement in the present moment.

The materials then (i.e., the canvas, the paint, the experiment, laboratory task, etc.) they are called the media. The degree of will-power then leads the creator towards the absorption with the task, in the form that he describes as engagement. It is here where May (1975) differentiates the genuine form of creativity with the pseudo form (otherwise called exhibitionistic) in that it lacks the encounter, eventually leading to Escapism.

Rollo May further elaborated the concept of the encounter in chapter four of his book, in which he posits that the creative act is an encounter between two poles, the subjective pole (which is the person) and the objective pole (the world or reality). In other words, the polarity between “being and non-being” (p.78), where knowledge and meaning is created.

As he further elaborates, the significance of a poem or painting is not that is exhibits the thing itself, but that it shows the creator’s vision as a result of his/her encounter with the reality. He adds, the importance of the creator’s receptivity, being vigilant enough to hear what “being may speak”. To be able to do so, the creator needs to be sensitive enough to incorporate the emerging vision; attentive enough to find the proper time for action; engaged in active listening to listen to the answer; alerted enough to scour the words or the emerging idea; and patient enough to allow the creation to proceed organically (p.81).

In this encounter, consciousness is intensified, and the polarity of the objective reality and subjective experience creates an ecstatic sense of meaning. As he notes, in the dichotomy/polarity between the objective and the subjective, it is often the sensation of anxiety. Interestingly, May (1975) describes “mature creativity” as different from childish creativity, in the sense that there are aspects of tension, struggle, and constructive stress that need to be confronted and dealt with if joy is to be felt from the creative output. This notion is in contrast with playing, where is described as an encounter in which the anxiety is briefly bracketed.

May (1975) brings a very interesting concept regarding the book of Genesis, where there was order out of chaos. As he mentioned, the first humans chose the ‘broken’ universe to get joy from their encounter and form into order. They would confront their anxiety and use it to create their chaotic universe close to their wish. Specifically, May speaks about the encounter by confronting the anxiety to the degree that during this encounter, “our sense of identity is threatened; the world is not as we experienced it before, and since self and world are always correlated, we no longer are what we were before” (p.93). As he further described,

Creative people, as I see them, are distinguished by the fact that they can live with anxiety, even though a high price may be paid in terms of insecurity, sensitivity, and defencelessness for the gift of the “divine madness”… (p.93)

As May added, the creative people exhibit courage to not avoid non-being, but through the encounter, they push it to create being. They try to knock on silence’s door to ask for music; they hunt meaninglessness to create meaningfulness. Chaos, therefore, needs to be endured, and the perplexity and complexity to be challenged and be compelled to find order and meaning. This creative process can be manifested in the therapeutic existential encounter as well.

The Existential Encounter

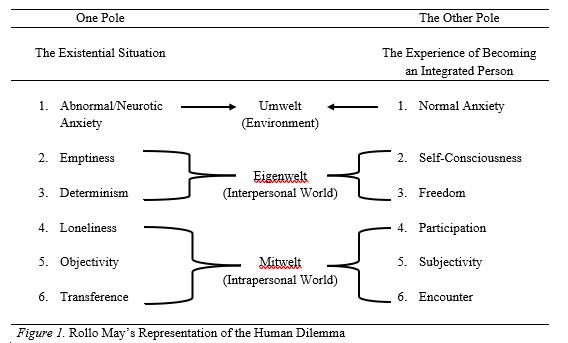

Here, May proposes that the world we live in is composed of two poles, which poses a human dilemma. This dilemma is that which comes out of the individual’s capacity to experience the self in both an object and a subject simultaneously (McEniry, 1972, p.69). It is within this dimension that the encounter happens. May used the classification from Ludwig Binswanger to describe the Umwelt (environment), Mitwelt (interpersonal relationships), and the Eigenwelt (intrapersonal world). From the bipolarity of the two poles, the following figure arises:

According to May (1977, pp. 192-200), normal anxiety is the reaction which is appropriate to the external threat; defense mechanisms (i.e. repression) are not involved; and can be consciously confronted productively. On the contrary, neurotic anxiety, is an inappropriate reaction to the external threat; defense mechanisms are present; awareness is inhibited due to subjective internal psychological patterns which makes a person vulnerable to a potential threat. Under the experience of neurotic anxiety, the sense of emptiness and meaninglessness is present. Here, the calling is to find meaning in a world that is bereft of it. Such was the purpose of the logos in Victor Frankl’s search for meaning towards self-consciousness and meaningfulness (Frankl, 1959).

McEniry (1972) in his dissertation further elaborated on the contents of the two poles in much detail. In May’s work, the encounter is another word for relationship, to emphasize that in the therapeutic framework, the work is much more than a relationship. In this encounter, we as therapists “throw” ourselves into therapy with the client. As McEniry stated, the encounter happens when the patient becomes conscious of Binswanger’s three worlds with the therapist. This is the position May holds, that the human dilemma is being resolved because of the therapeutic encounter, and “by integrating a creative response to normal anxiety, participation, and subjectivity, one person encounters another” (McEniry, 1972, p. 99).

The encounter in the existential approach is distinguished in the way that it takes the encountering experience seriously (May, n.d., as cited in McEniry, 1972, p. 100). In this existential therapeutic encounter, May proposes four elements, crucial to his thesis: (1) The element of empathy (2) the element of philia (3) the element of eros, and (4) the element of agape. These are further explored by McEniry in his doctoral dissertation. The creative and therapeutic encounter have a similar process, to reach the total encounter.

The Total Encounter

May, (as cited in McEniry, 1972, pp. 110-111) distinguished between the aforementioned four elements, the creative aspect of eros in the therapeutic encounter. Associating myth in his understanding, he noted that the Greeks viewed Eros as a god who, by shooting his arrows into humans, led them to either healing and joy or to anguish and despair. They believed that this god would lead someone to higher forms of creative potential and human love towards the creation, restructuring, and re-discovering of oneself. In May’s perspective, eros is the most significant ingredient of creativity, and when it is separated from it is can lead towards destruction. In his words:

The encounter with the being of another person has the power to shake us profoundly and may be potentially anxiety-arousing as well as joy-creating. The therapist is often tempted for his own comfort to shield himself from the encounter and its power to move him by abstracting himself, by thinking of the other as “just a patient”, or by focusing only on certain mechanisms of behavior” (May, as cited in McEniry, 1972, p. 119).

Concluding Remarks

In between the polarity of this encounter, the person is able of knowing, experiencing, feeling, and affirming oneself towards reaching a rich and meaningful existence. Similar with the creative encounter, the therapeutic encounter involves sharp awareness and being caught up in the encounter. Engagement of action then commences which opens the gate to the chaos of our minds with the premise of it to be endured and extract/construct meaning out of it. Values of patience, sensitivity, attention, and active listening within the polarity of being and non-being, are what contribute to the timing of the creative output. This is what, essentially, leads us toward transformation, since in order for something new to be created, the tension between both thesis and antithesis needs to be confronted to give birth to synthesis; and from this ultimate encounter, meaning and joy is eventually created.

References

Frankl, V. E. (1959). Man’s search for meaning. . Massachusetts: Beacon Press.

Gaut, B., & Kieran, M. (2018). 1. Philosophising about Creativity. In B. Gaut, & M. Kieran (Eds.), Creativity and Philosophy, Kindle Edition. London and New York: Routledge.

Kampylis, P. G., & Valtanen, J. (2010). Redefining creativity—analyzing definitions, collocations, and consequences. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 44(3), 191-214.

Kaufman, J. C., & Sternberg, R. J. (Eds.). (2010). The international handbook of creativity. Cambridge University Press. doi:https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1017/CBO9780511818240

May, R. (1975). The Courage to Create. New York: W. W. Norton & Company Inc.

May, R. (1977). The Meaning of Anxiety. New York: The Ronald Press Company.

McEniry, R. F. (1972). The existential approach to encounter in Rollo May. Ohio: The Ohio State University.

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). The concept of flow. In Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (pp. 239-263). Springer, Dordrecht. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9088-8_16

Runco, M. A. (1997). The Creativity Research Handbook (Perspectives on Creativity). Hampton Press.

Runco, M. A., & Pritzker, S. R. (Eds.). (2020). Encyclopedia of creativity. Academic press.

Sternberg, R. J. (Ed.). (1999). Handbook of creativity. Cambridge University Press.

Walia, C. (2019). A dynamic definition of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 31(3), 237-247.